As technology evolves at a rapidly-increasing pace, a familiar phrase is often echoed each time a new product hits the market: “They don’t make them like they used to.” This sentiment, often repeated over the course of an item’s lifetime, encapsulates the consumer’s anger about quality and longevity.

Rather than delivering a product that keeps a consumer happy for a lifetime, companies opt to intentionally lower their commodity’s lifespan in a relentless pursuit of profit, forcing the consumer to upgrade to the latest technology.

Continuous abuse by companies have only hurt consumers, eroding their trust in a brand and undermining the notion of quality craftsmanship. With more complex and advanced technology integrated into a product, simply repairing it oneself is not an option, leading to a monopoly of sorts within the repair market. Instead of having a product that lasts for years to come, consumers are faced with a perpetuating cycle of consumption, fostering a culture of waste while straining household budgets.

Planned obsolescence is not a new concept, having been introduced in 1924 as a marketing trick by Alfred P. Sloan Jr. to boost General Motor sales. Slight changes and refreshed appearances every yearly release drew in new consumers and increased profits.

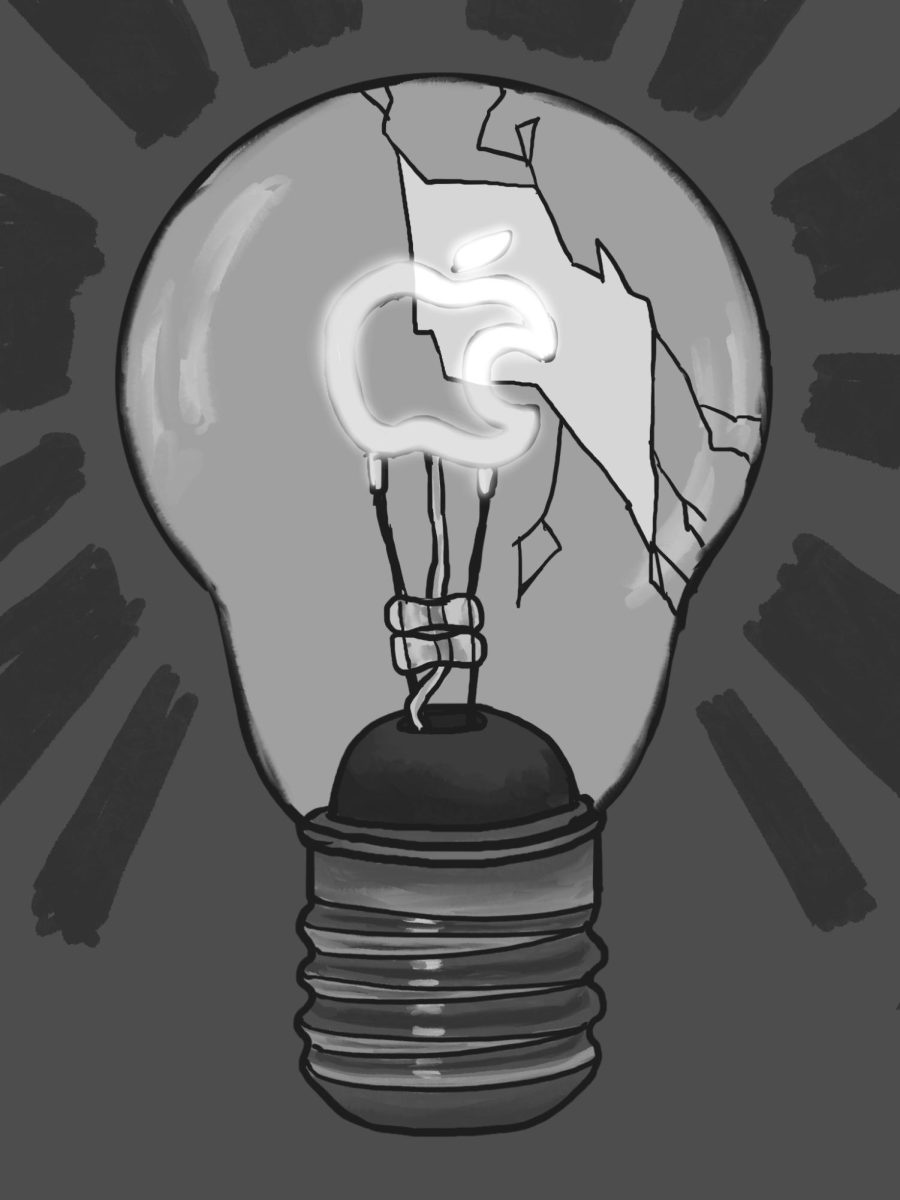

Automobiles are durable, however, and simply conjuring an error within such a product was not economically feasible. Thus, planned obsolescence was seen more in household products, with the infamous Phoebus Cartel employing such strategies in lightbulbs.

Comprising of companies such as General Electric, Philips, Osram and Associated Electrical Industries, the cartel controlled the lightbulb market and lowered the lifespan of the bulbs so consumers would buy more to replace the dead ones.

While energy-efficient light bulbs have since outlived the cartel, the concept has continued to exist within the tech industry. Smartphones, computers and other digital devices flood the market each year, enticing consumers with claims of upgraded features and newer designs at the cost of complex parts and manufactured deterioration.

Apple is infamous for employing this concept enmasse, with generations upon generations of charging cables changed per device. Its most recent case, as reported by NPR, was settled for “$113 million… over allegations that it secretly slowed down old iPhones.”

This is where the concept of the right to repair falls in. Starting as a grassroots campaign aimed at dismantling the stranglehold of planned obsolescence, the concept champions the consumer’s right to repair and maintain their own possessions. At its core, it advocates for a fair market distribution of original spare parts and necessary tools, with a build and design that allows for easy repairs unhindered by software programming.

The fight for the right to repair is not a matter of convenience or cost preservation, it is a fight against planned obsolescence and sustainability. According to the World Health Organization, “In 2019, an estimated 53.6 million tonnes of e-waste were produced globally, but only 17.4% was documented as formally collected and recycled.”

Millions of tons could be saved through DIY repairs, and it challenges the notion that products should be disposable by design. This concept reaffirms the consumer’s right to autonomy and ownership, fighting back against the tide of corporate greed.

Corporate greed, of course, being the primary reason behind the degradation of the American free market. Regardless of where products are manufactured, the cornerstone of American industry and progress has been the quality of the products. The steel, produced on the backs of the hardworking laborer, transformed the world.

If American nations no longer keep quality in mind, their products lose their power. Longevity leaves a lasting taste of satisfaction in the consumer’s mind. Success doesn’t just mean pumping money out of the pockets of ordinary citizens. It means satisfying them for the good of society.

Consumers have a right to use their products as they so choose and not be at the mercy of corporate giants who degrade its quality every passing year. Products should not be a “one-and-done” ordeal. They should be given care to last lifetimes until its usefulness is outlived. Customers should mend not end, and through the right to repair, they can fight its planned obsolescence and reduce waste for years to come.