In the past, I would have been inclined to write this panel like a congressman, filled with hot air, and speaking only to hear myself. This was a time in my life when I thought reading all the classic novels and learning all the schools and branches of philosophies was the surefire way to define myself. It was a way to seek self-validation for an ego I did not even know I had.

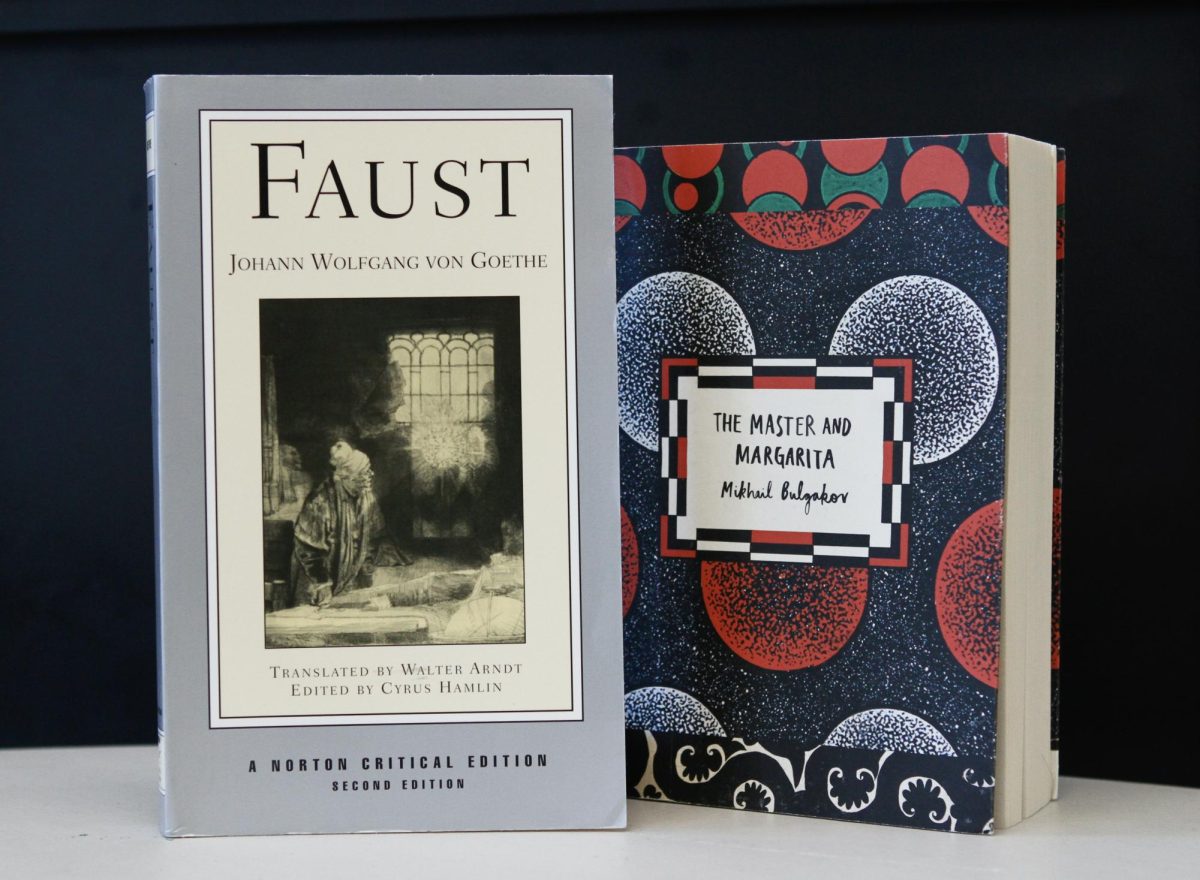

About four years ago, when I was pompous and pretentious enough to send King Charles into shock, I read “Doctor Faustus,” a play by the English poet Christopher Marlowe. I did not think much about it, or its characters, or anything really. I liked the satisfaction and air of superiority I was able to wear around others for a week or so, simply because I finished the book. It was not until this summer when I read “Faust” by Johann Wolfgang Von Goethe, that I understood how wrong I was for ignoring this masterwork.

“Faust” is the most classic tale in all of Judeo-Christianity to not be canonized in the Bible. It, like its predecessor, “Doctor Faustus,” is the story of a winded scholar in the German countryside, who sells his soul to the forces of evil in order to seek enlightenment. Goethe’s version came about two centuries after Marlowe’s telling of the story, but the idea of a tortured philosopher like Faust has been kicking around in German folklore for hundreds of years prior to its dramatization in an advanced European literary culture.

As such, the story of Faust is as much a cautionary tale as it is a folktale, superbly mixing elements of German rural mythology with Christian epics to create a well-produced final classic under the hands of Goethe’s poetic genius. It is so brilliant that I cannot seem to think about anything else ever since.

What sticks out to me is the way that Goethe portrays Faust’s character. Faust is deeply unhappy, drawn to consistently asking himself the question: what is the meaning of everything? He is so deeply chained by his library of massive spellbound books and academic works that all the life and passion is sucked out of him. Yet, he cannot seem to escape his inner curiosity and drive to be something greater than just a man.

Faust’s great sin is that he seeks to emulate God, to be the keeper of all knowledge. For this, he makes a deal with the Devil that if he cannot feel happy with access to all supreme understanding, then he would be the servant of evil for the rest of all time.

The ultimatum behind this contract represents Lucifer’s so-called “Great Fall,” canonized in the Old Testament, and it sets up “Faust” to be a brilliant tale of redemption and spiritual reclamation at the hands of Doctor Faust.

This was 200 years ago. Goethe’s retelling of this classic Christian tale of good versus evil has not aged brilliantly. It needs a great complement to lock in its understanding in the modern day, so I offer to the reader one of the best books I have ever read: “The Master and Margarita” by the Soviet writer, Mikhail Bulgakov.

The Devil – codenamed Woland – is in Moscow, Saint Petersburg and Yalta for one crazy week in this wild novel. He comes with a troupe consisting of one snake-like man, a very sassy cat, a depressed succubus and a smooth-talking valet dressed in all purple. Together, they raise chaos, levy death, spawn peculiar circumstances and get to meet the two lovers, the Master and his partner, Margarita.

Of course, the main character of this novel is The Master, a writer who seeks to retell the story of Pontius Pilate, the Roman governor of Judea who sentenced Christ to his death. The Master is the modern day Doctor Faust, a tortured scholar who feels deeply unhappy with his work, who resigned himself to life in an insane asylum rather than face public judgment for his work.

Bulgakov in focusing on The Master, creates three intricate storylines that all interweave and connect with each other: Woland and his troupe’s ironic punishments for the sinners of Moscow, the love-story between The Master and his biggest fan, Margarita, and the sins of Pontius Pilate and his eventual redemption.

Rather than hold one story of redemption to itself like in Goethe’s retelling of Faust, Bulgakov’s version has three different tales of absolution. Bulgakov’s writing is lyrical and deeply satiric, and his characteristic voice feels like I am reading out of a magical poem in which every line is sweet and beautiful. I could not get enough of him!

I revere Goethe for similar reasons, but his writing is so archaic it is difficult to understand. For that reason, I would recommend that prospective readers familiarize themselves with Faust, the folktale, move on to Bulgakov’s retelling of the story, and then work their way to Goethe’s version, so that they could truly appreciate the story’s genius.

Now comes the time where I must finally address my past sins. I resonate deeply with Doctor Faust and The Master because of my egotism. I tortured myself for hours on hours in my room reading books I did not like and I did not care for. I have read Melville, Chaucer, Dickens, D.H. Lawrence, Plutarch, Virgil, Dante, Aristotle, George Eliot, Austen, the three Brontes and many more.

I hated them all. I wanted to burn every word those poor and bloated writers even dared to put on the page.

I tortured myself to the point where I just put down books in general. I spent my sophomore year barely managing to fulfill my reading expectations for this panel and parotting literary articles from undergraduate students.

Goethe and Bulgakov’s retelling of Faust teaches us in the modern day to do what we love and to only follow our passions. I love to read! I love the learning element of it so much that I just want to engross myself in everything I read from now on and truly love it for what it is, not because of some voice in the back of my head that tells me satisfaction, true understanding and academic excellence is there for me if I do.

This is the lesson that Faust teaches us. To do what you love and to love doing it.