Known for his poor inclination toward well-worn fashion, Stendhal is a French writer who stands alone in history as an enigmatic and strange figure.

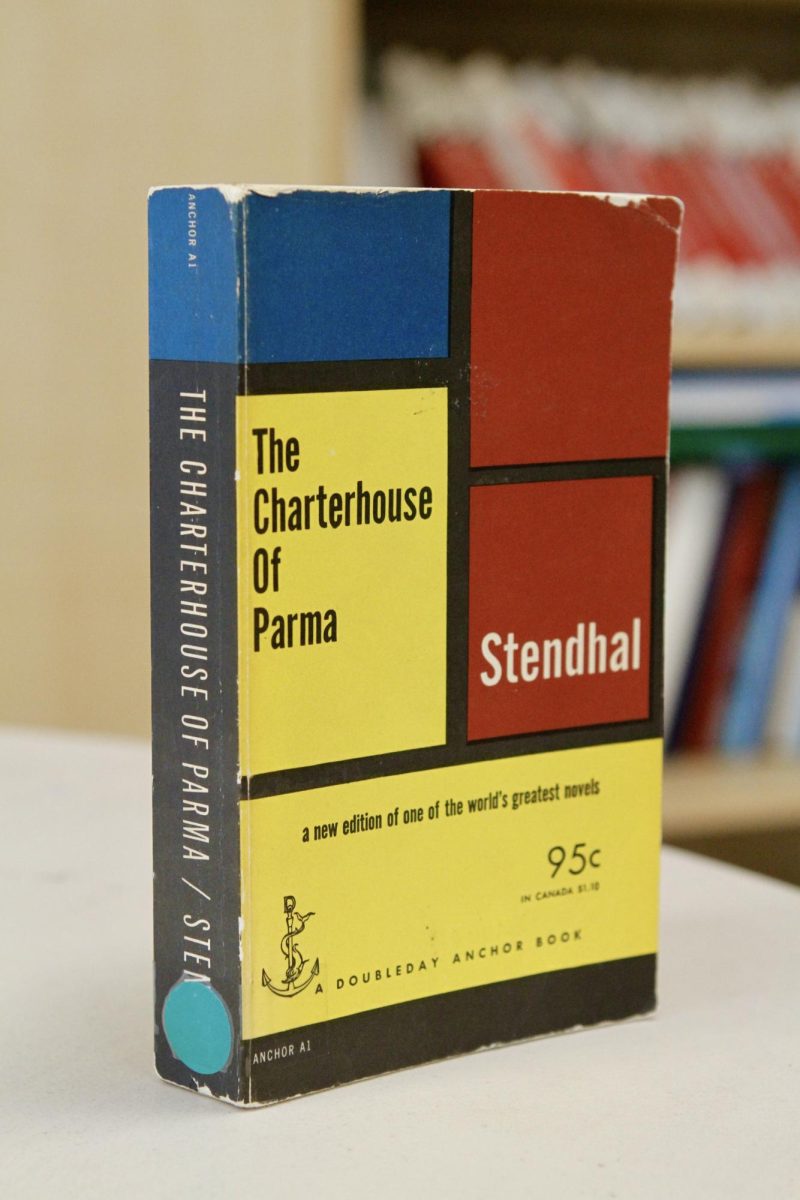

His great classic, “La Chartreuse d’Parme,” translated either as “The Monastery of Parma” or “The Charterhouse of Parma,” stands alone as his great contribution to the European literary canon. I picked it up about a month ago, off of a clearance aisle in a bookstore, engrossed by the fact that I had never even heard of Stendhal or his work. I have to say, reading it felt like I had discovered a great secret that only I was let in on.

As such, I believe that “La Chartreuse d’Parme” is best if the reader goes into the novel knowing absolutely nothing about its plot. I do not want to be the idiot who ruins that experience for them.

I found myself at a crossroads when I read this novel. Stendhal had such a different writing style than anything I had ever read before. He was a 19th century writer, and I expected him to be as boring and pedantic as one. And he was. Yet I liked it. I enjoyed his expanded dialogues and detailed narratives more than anyone should really.

“La Chartreuse d’Parme” was published in 1839. As I understand, Europeans loved a good hero’s tale at this time. This is not the first time I have talked about a Byronic Hero – lover of adventure, fine things and exuberant arrogance – but last time I made the mistake of not understanding what it really means to be this type of hero. I believe this is the key question Stendhal asked himself when writing his masterpiece.

So what does it mean to be a hero? People proudly declare their heroes publically, and we always see stories of “real-life heroes” on the five o’clock news. But are any of these people actually heroes?

As I said, the Europeans of Stendhal’s day loved to hear stories of heroes and their exploits, but it is clear that he did not believe in this norm. As such, he has received an interesting position in literary history. I think this is why Stendhal’s writing style is so significant to me – he did not subscribe to the conventional norms of Romanticism or its literary stylings.

In every novel there is an invisible pulse behind every scene, every character and every conflict. It seeps into the minds of characters and it dictates their actions. When we look at literature, however, the pulse changes based on the author’s intentions. In other words, this is the theme.

In the Romantic era, the drive and motivation were the forces of love, mystery, heroism and faith. What is so brilliant is that Stendhal did not conform. The driving force behind “La Chartreuse d’Parme” is not Romantic fiber or desire, but instead the worst qualities of his characters, their foibles and their unique psychologies. In spite of all this, Stendhal has made his main character, Fabrizio del Dongo, a hero.

And what a brilliant hero he is. He makes mistakes and he can be, at times, very incompetent, but Stendhal still idolizes Fabrizio for who he is – simply human.

It is so very easy to be swept up in the fervor of heroism, to love and to idolize great characters and their valiant exploits. These characters become the most iconic in our Western culture, and they make for great stories. In every Robin Hood, however, there lacks something real and intrinsically human.

This is why Stendhal’s writing sticks out to me so greatly.

He teaches us to love each other for who we truly are. We are not all great heroes. Most of us are all rather ordinary. So, what makes a hero? Like Fabrizio del Dongo, it is the courage to be unafraid of being human, of being different, of having the strength to be the person you were born as.

Heroism is not who you can be, but instead who you are.