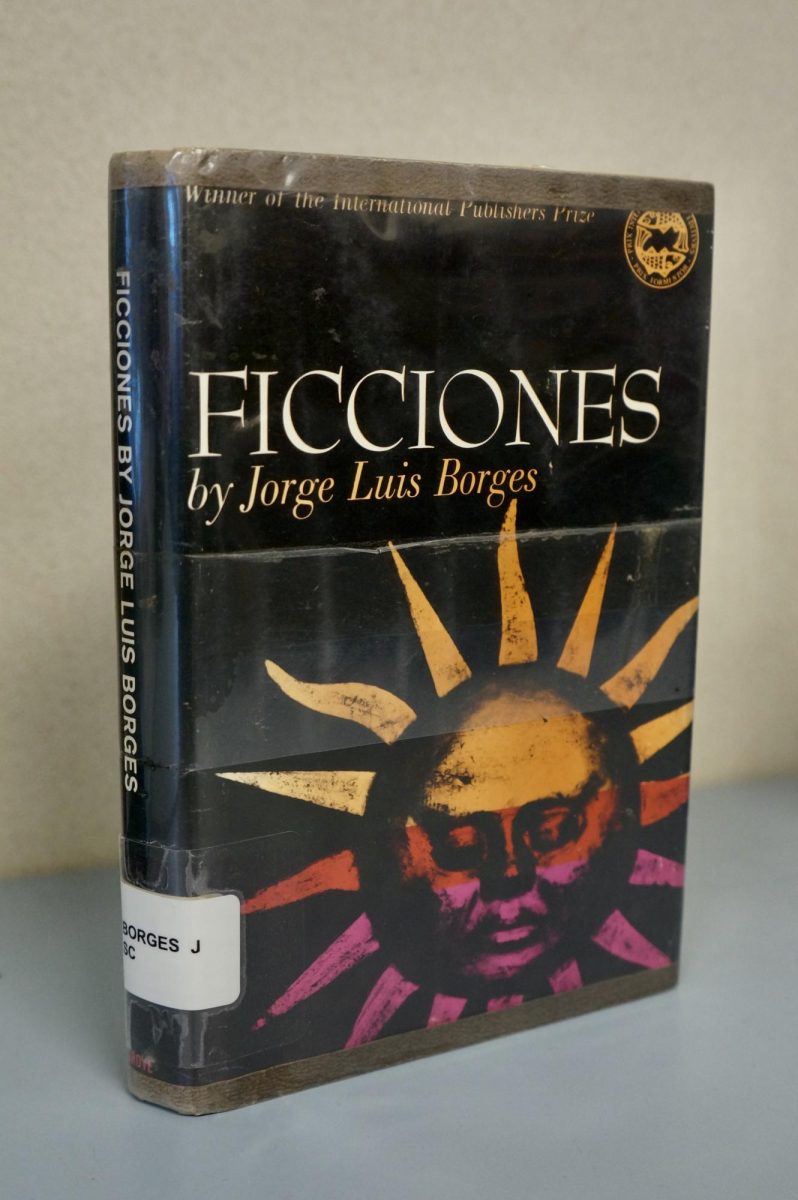

I have gotten a lot more into short stories recently, inspired by my deep and cemented love of Raymond Carver. I looked around for something really impactful, and it seemed to be that the internet and word of mouth pointed me toward the Argentine, Jorge Luise Borges. His classic “Ficciones” is a collection of 13 short stories, the supposed embodiment of the post-war spirit of Irrealism and Surrealism.

Originally released in 1941, Borges entered the literary canon of impactful Latin writers who have an influence stretching deep into the 21st century. Despite the fact that Borges has been a paramount figure in modern literature, I could not shake the feeling that something was deeply wrong with “Ficciones.” Frankly, I do not believe Borges even knew what he was writing in “Ficciones,” let alone even thought about what he was writing.

“Ficciones” reads like the deranged ramblings of a lunatic. It is a discombobulated mess and fails to coordinate any underlying coherent thoughts of Borges. I found myself reading the lines and having tiny fragments of sanity shoot up at my face, but it all amounted to nothing.

Literature can be confusing. It can be weird. It can be peculiar. It can be so many different off-brands of nontraditional, but the one thing any literary work cannot be is incomprehensible. And that is unfortunately what Jorge Luis Borges accomplishes in his work.

Knowing this, I tried to grasp some more academic receptions of “Ficciones” and all I could find was the vague statement of Karl Ove Knausgaard, author of the literary trilogy “My Struggle,” which I have grown enough to realize that the unfortunate German translation of this name is a poor title for any work. Anyway, the Norwegian writer calls the first story of Borges’ collection, “TIon, Uqbar, Orbius Tertius,” the best “short story ever written.” From here, I have realized that this tends to be a common form of praise granted to “Ficciones.”

Instead of doing my normal spiel in which I attempt to grant and decipher philosophical truths out of a literary work, instead, I am going to use Borges’ work as a teachable moment.

By definition, the entire literary community that has given so much praise to Borges’ “Ficciones” is a highly critical, skeptical, almost cliquey group of writers. This community praises itself as an academic one. Of course, within academia there resides the absolute worst egotism ever seen. So easily influenced are these egoists, these vain and insecure individuals who will do absolutely anything to fit in.

Dazed and confused, these so-called academics were really left without any clue after WW2. It became trendy to criticize tradition, to stand out, to really hate authority and to ferment revolution wherever it lay. There truly have been some glorious names who have done such an amazing job in this department: Jack Kerouac, Allen Ginsberg, Ken Kesey, Sylvia Plath, Tove Ditlevsen, James Baldwin and so on.

I think that knowing what was in and what was absolutely not in, critics saw Borges’ bold and nontraditional style and confused his alien outlook as being revolutionary and intelligent, like the work of the brilliant writers named above. The problem is that Borges’ work does not exude these amazing qualities. I do not actually think anyone who has ever proclaimed to like “Ficciones” ever actually did enjoy the book. In fact, I would go as far to state that they just boldly said so in an attempt to fit in because that was what all the “cool” critics were saying.

I understand the irony of me actively writing this panel and entering myself into a worldwide community of literary criticism. I know I referred to my own community as a conglomeration of egotistical windbags. I do not regret it though, unlike the time I spent reading “Ficciones.”

As such, let Jorge Luis Borges’ “Ficciones” stand as a hallmark for what not to do when writing fiction.