If in 20 years someone asked me to explain how a book with a talking gorilla named Ishmael educating an unintelligent, slow, dimwitted man on the nature of society and anthropology was in any shape or form significant to me, then tell my family I am going to be late for dinner.

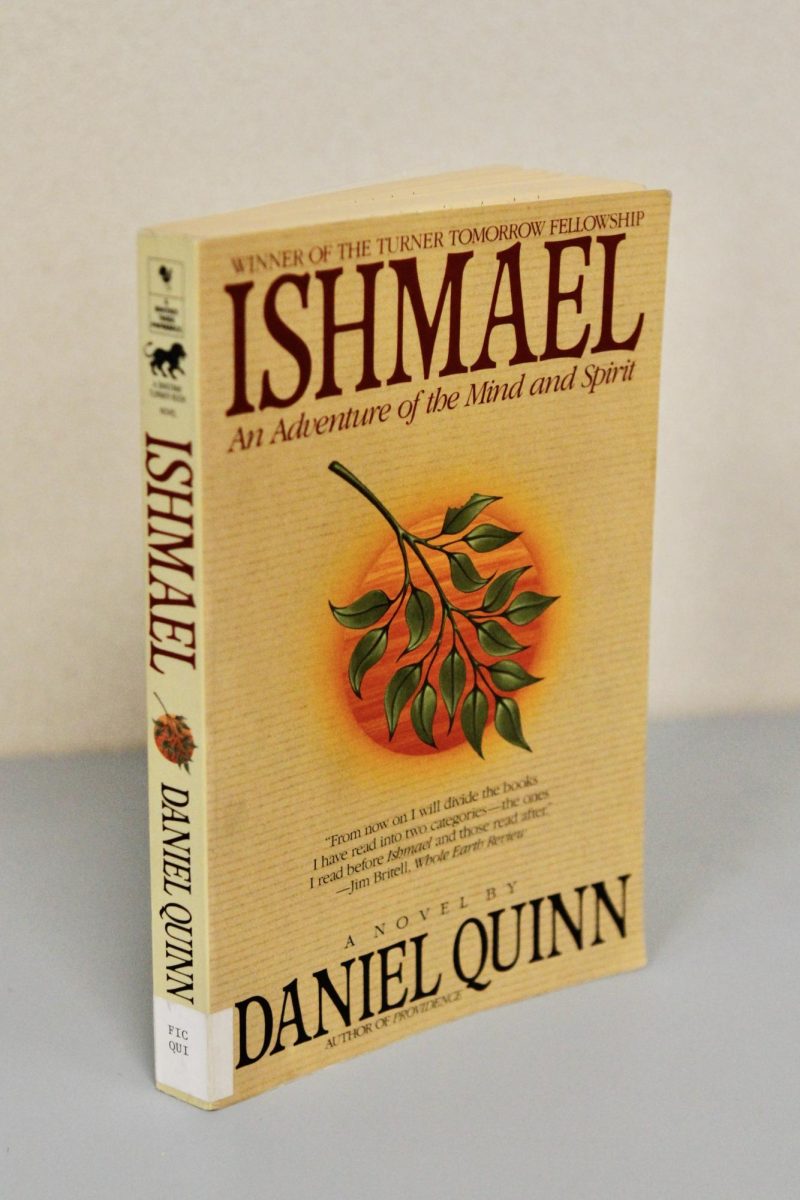

There is absolutely no shortage of topics to talk about when it comes to Daniel Quinn’s 1992 novel, “Ishmael.” I have read some strange books in my limited years, but none of them come close to Quinn’s work.

The premise is simple. A rescued circus gorilla educates himself on all of human history, mastering the English language while he is at it. And the very beginning of his rapid evolution starts with being given his name: Ishmael. From the sounds he recognizes, objects become things, things become concepts and soon, the entire world spans out in front of him.

Yet, Ishmael has a problem. He understands humanity better than any other, so he puts out an advertisement in a local paper offering a tutorship to a mentee who wants to “save the world.” Undoubtedly so, our main character jumps at the opportunity, only to find himself in the presence of Ishmael.

I cannot say more about the story from here. That is up to the reader to discover for themselves.

Quinn’s work brings to mind millions of years of human progression. Once I was sitting in a history class and the kid next to me told me the class was pointless and asked why anyone would need to learn history. Do not get me wrong, I dismissed the other student’s comment quickly enough, but he did ask a valid question: Why does anyone need to know anything?

Quinn writes and spends so much time focusing on the nature of evolution that it is hard to not get swept up in the writing and forget the very basis of his beliefs.

In a sociology class, my professor asked me the question: how do you know what you know? Now, I know what she was referring to (or do I?), as far as epistemology goes, but I tuned out for the rest of that day. As much as I thought about it, the more confused I got. Going home, I went online and bought a bunch of copies of different philosophical texts that were supposedly going to help answer my question.

Hegel did not help. Nor did Wittgenstein. All I had done was wasted several months of my time and 50 precious bucks that I could have used for practicality, such as gas or groceries.

I have come to realize that people truly do not know anything. I do, however, see the irony there. Herein lies the point that Quinn is trying to make along with many other folks from the same era.

We could waste our lives trying to find an answer to so many questions – what car to get, insurance premium to buy, the blue or the red, which major to choose and a whole other bunch of painstaking questions that take the life out of us. At the end of everything, we will all be old and wrinkled and maybe gray. And what did the lifelong search get us? Nothing.

Happiness and fulfillment come from the choices people do not make. Anything good in this world is handed to someone whether they want it or not. It is up to the self to make the world what the self wants it to be. When Ishmael says to the world that he aims to save humanity, whatever deliberations he makes afterwards, is just chaff. But the process of coming to look beyond words and texts and dialogues – therein lies his saving wisdom.

To start off the new year with a good read, I highly recommend “Ishmael.” It might just save someone’s life.