Having come from Glasgow, I have found the strength of the Scottish identity to have been diluted in centuries-long conflicts regarding politics, confusing naming conventions, ethnicity and nationality. In 2014, we voted to remain an integral part of the United Kingdom, and it is hard not to see why. The conflict extends the national realm – it appears to be a part of us.

I am reminded, of course, by the sight of the British flag above any and all mentions of the Scottish one at any available chance: atop national relics, important buildings and infamously so, on the backs of Scottish athletes. The psychology of being part of the supra-ethnic British empire is ingrained within us.

But there are parts of the Scottish identity that speak to me. Football (soccer), rugby, music and a courage unlike any I have seen anywhere else. And how can one forget the infamous Scottish language?

It is recognizably English, but the implementation of phonetic spelling completely changes the look of it. For my own dignity, I will not offer an example, but anyone can easily find examples of the language in practice.

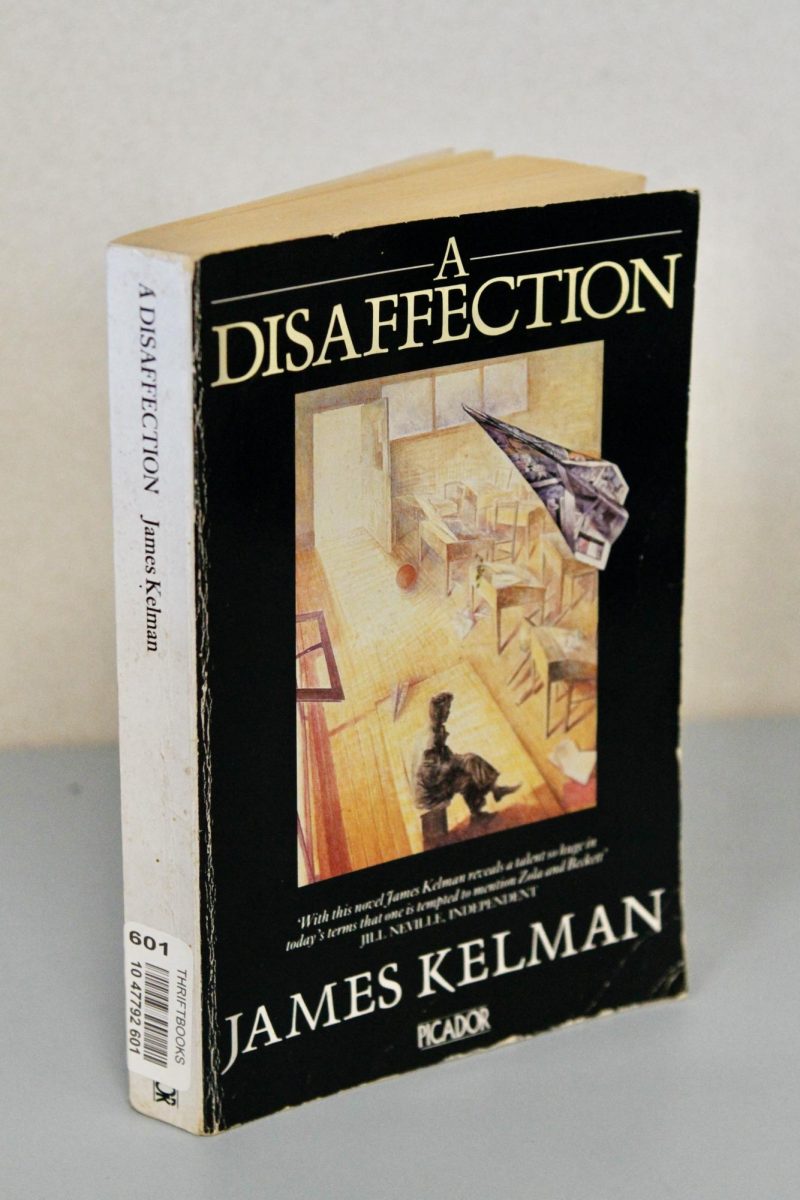

Books that exemplify the Scots language are rare to find, but when found, offer an insight into my culture that I have often turned a blind eye to. When I discovered “A Disaffection” by Scottish author James Kelman, I was placed on a pretty fun adventure.

Writing entirely in Scots and implementing “flow-of-consciousness,” Kelman places me in the brain of schoolteacher Patrick Doyle, who lives in Glasgow while wallowing in his complete and utter sadness. For anyone unfamiliar with “flow-of-consciousness,” it is basically a series of the longest run-on sentences ever, a frantic approach to each paragraph, all the while placed in a non-linear fashion that is oftentimes confusing and hard to tackle.

“A Disaffection” is a riddle. But when I cracked the code, understood the motifs and elements of Doyle’s life that he latches onto, there was a deeper message within.

James Kelman was actually nominated for what is essentially Britain’s own version of the Pulitzer, the Booker Prize, for this novel in 1989. I would not go as far as to sing his praises and award him for this book, but I can share what I found to be lasting and significant.

“A Disaffection” is an exploration into one’s purpose and calling in life as Doyle struggles with being a teacher. At the beginning, he finds a pair of bagpipes (fitting), and is continuously drawn toward his leaving of the teaching profession in exchange for becoming a piper.

Desire becomes a part of him. When his life becomes too hard, Doyle moves continuously toward the piper fantasy but shakes it off as absurd. In this sense, the novel is also an exploration of hedonistic fantasy to shake off the bounds of obligation and search for what the soul truly wants.

This reminds me of another infamous book written in Scots with a profound effect on me: Irvine Welsh’s “Trainspotting.” Without going into too much detail, Welsh’s main character struggles with the chains of society, mocking the choices of standard, middle-class life. “Choose life. Choose a job. Choose a career. Choose a family. Choose a big-screen telly” and so on – this being the infamous dialogue within the movie adaptation of “Trainspotting.”

I have not forgotten those words, and in the realm of Kelman’s work, they flew right up at my face once again.

There is a desire within any of us to wave off our obligations and just live off the land. I cannot remember who it was, but once when asked about my plans after high school, someone was surprised to hear that my goals were not to just sit on my farm and shoot bottles all day. As tempting as it sounds, I know deep within me that I cannot do that.

Young folks misinterpret a hesitation toward life and necessity all the time. I see young guys idolize infamous anti-heroes simply because they chose to be different, not understanding that the entire point of the anti-hero is to highlight the wrong choice.

The choice to be great, to overcome that immature desire to relinquish responsibility, is what makes one great. Choosing life, or choosing to live and work in a sustainable career, is not the wrong choice. Overcoming adversities is what makes people in this post-industrial world truly special.

In this way, I cannot relate to Patrick Doyle, or any of the other characters. They represent cowardice. The choice lies within every human to be great.

So this year, choose life. Or choose to read James Kelman’s “A Disaffection.” It’s immaterial to me.