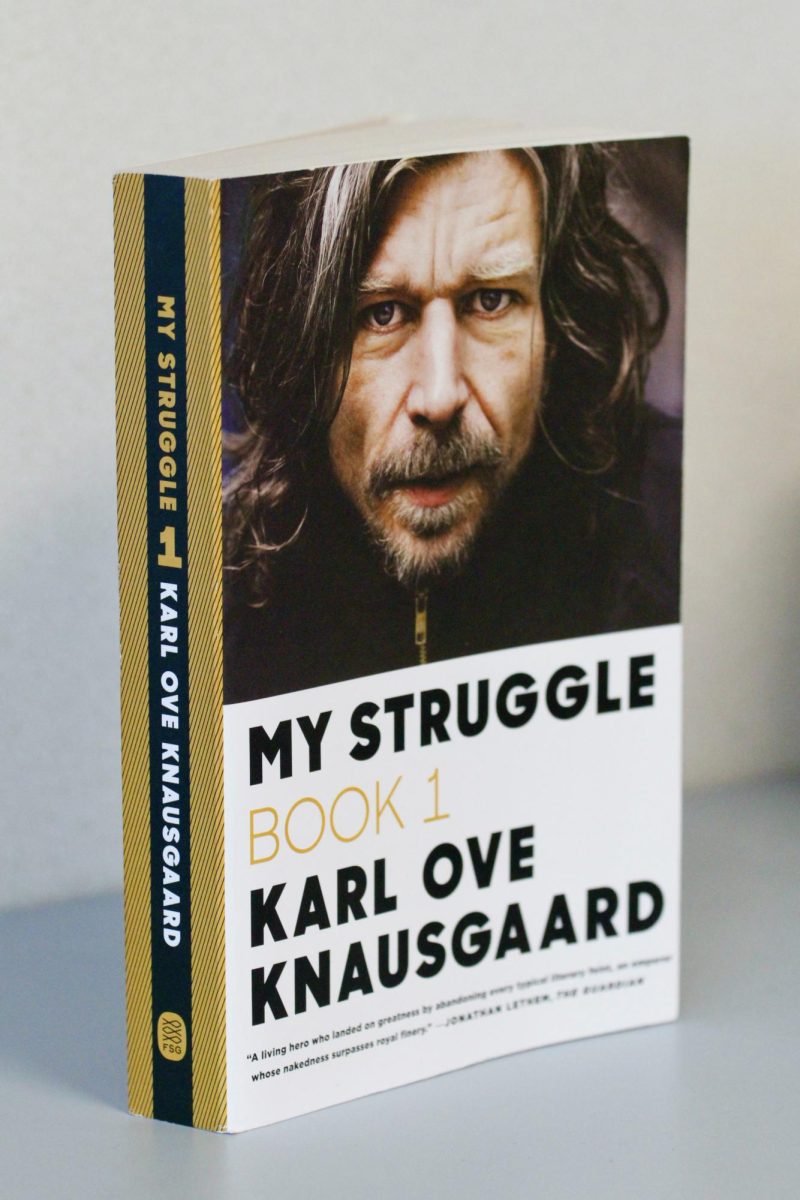

Walking down the aisles of a bookstore and seeing a book titled “My Struggle” is one jarring eyecatcher. I thought I was in the presence of one of the most evil books ever written. Out of pure curiosity, I picked it up, only to see a familiar name on the front: Knausgaard.

A few months ago, I criticized Karl Ove Knausgaard for being yet another elitist academic who didn’t really know what they were talking about. The idea was that I disagreed with his take on Borges’ “Ficciones,” to which I thought it was an appropriate reaction to completely dismiss him.

Never have I ever been so wrong about someone.

“My Struggle,” a six-volume autobiographical drama written by Knausgaard, tragedizes his own life through his highly critical, nuanced and relatable philosophy. He can take the littlest of his experiences and turn it into a story dripping with profundity.

Knausgaard’s writing style is highly Proustian: close and personal, dramatic yet blissful, lavished with solitude, heartfelt and overpowering. But he’s not pretentious. Something about him can be described as masterfully Nordic – cold and plain – as would befit a Norwegian writer (Tarjei Vesaas, Henrik Ibsen and Ingrid Undset among many others all support this claim).

In many ways, “My Struggle” is a book about Knausgaard’s relationship with his father. The two of them had a strained relationship. Through Knausgaard’s eyes, his father helped define him as a human being. Along this line, the autobiography also defines Knausgaard himself.

There’s nothing to really spoil about the book. His stories are rather ordinary, common to many teenagers. I didn’t learn about his life. Instead, I saw the many lives in his life morph into the many lives of my life as he covers the motifs that transcend all individual persons: love, death, fear, courage, bravery, anger.

But there’s one thing in “My Struggle” that I’ve never quite seen before in any piece of literature.

Imagine the face of the living man. Then, similarly, imagine the face of the dead man. Realistically, most would say there are inherent differences in complexion, muscles, structure, etc. But above all, the form and build are entirely the same – two eyes, a nose, a forehead, a jaw and so on.

Around him Knausgaard gives everything a face. Literal faces, per se, or on concepts, or ideas, or on things that he can’t quite understand. Everything has shape and form. But something transcends shape. There is a spirit in every object that connects the viewer to it.

So once again, what is the difference between the live man and the dead man’s face? Not shape, nor form.

Whether it is purposeful, accidental, or even an unconscious decision of his, almost everything is described with a face – Knausgaard’s first love, his first child, reading a book, listening to a disco record – something that connects him to it, wherein he can explore his mind, self and understanding of everything. The face is the connection to all knowledge on this planet. Knausgaard’s opening monologue tells more about this.

His choice to name his autobiography “My Struggle” is entirely purposeful. He is no Nazi, so why name his autobiography the very same as Hitler’s? Here is where things become difficult to write about.

I grew up with the stories of Nazi occupation in Greece from my father, who heard them from his father, and his father. In America, it is difficult to understand just how catastrophic Hitler’s rise was for the European people. For many Americans, a relative went off to fight, came back home, married, lived in prosperity and now his ancestors enjoy a middle class life one can’t complain about.

The rise and fall of the Third Reich was the most catastrophic event in European history. Everywhere, the chains of former Nazi domination can be seen. Nothing more so than the current rise of Europe’s far-right. What started as Skinheads and Nazi gangs within Europe’s most deprived urban centers has now become a well-organized political specter of fascism, ultranationalism and racism.

In 2011, three years after the publication of the first volume of “My Struggle,” far-right Norwegian nationalist Anders Breivik slaughtered 77 people in cold blood.

Knausgaard, who had grown up in the shadow of a Nazi-occupied Norway, lived miles away from the nation’s most infamous Nazi collaborator, Knut Hamsen, who was known for the horrors of the far-right sphere of influence. The shooting left a profound mark on Knausgaard.

In The New Yorker, Knausgaard wrote one of the most prolific and impactful think-pieces that I have ever read. Above all, I’d highly recommend reading his piece, titled “Anders Breivik’s Inexplicable Crime.” In it, he describes a similarity between Hitler’s “Mein Kampf” and Breivik’s massacre. Their dialectic changes language and thought itself, erasing the “you” and replacing them with “I” and “we,” reflecting an inexplicable act of blindness – the devaluation of another life.

In other words, Knausgaard is giving a face to evil. He is humanizing Breivik. He is humanizing Hitler. He is humanizing all who hate and all who commit the “inexplicable act.” Some have even gone so far as to say Knausgaard is comparing the early life of Hitler to his own. I don’t know that for sure, but in his eyes, within every evil man lies the heart of an innocent 12 year old. No human being is born evil.

What connects us all to evil is the face of it. Knausgaard chose to represent evil with a face because faces connect everybody on this planet to the universal emotions and experiences: love, death, fear, courage, bravery, anger. Through his title, he is defining human nature… with a face.

So once again, I ask the question: what is the difference between the live man and the dead man’s face?

The answer isn’t shape. Nor is it form. It’s not the hands of the mortician who preserved the dead man, nor the parents who brought the live man to life.

There is no difference. Within and all around, millions of faces are seen each and every day. Whether in the literal or the Knausgaardian sense, there are so many things each individual seeks to represent what is known to be human nature – millions of faces within faces, all that is known to be and what will be.

I have not read all six parts to Knausgaard’s prosaic epic yet. One day I hope I will. He’s an extraordinary writer. Whatever commendations I can give, I have already. So to commemorate the commencement of spring, I’d highly recommend everyone check out anything written by Karl Ove Knausgaard, a truly amazing writer.