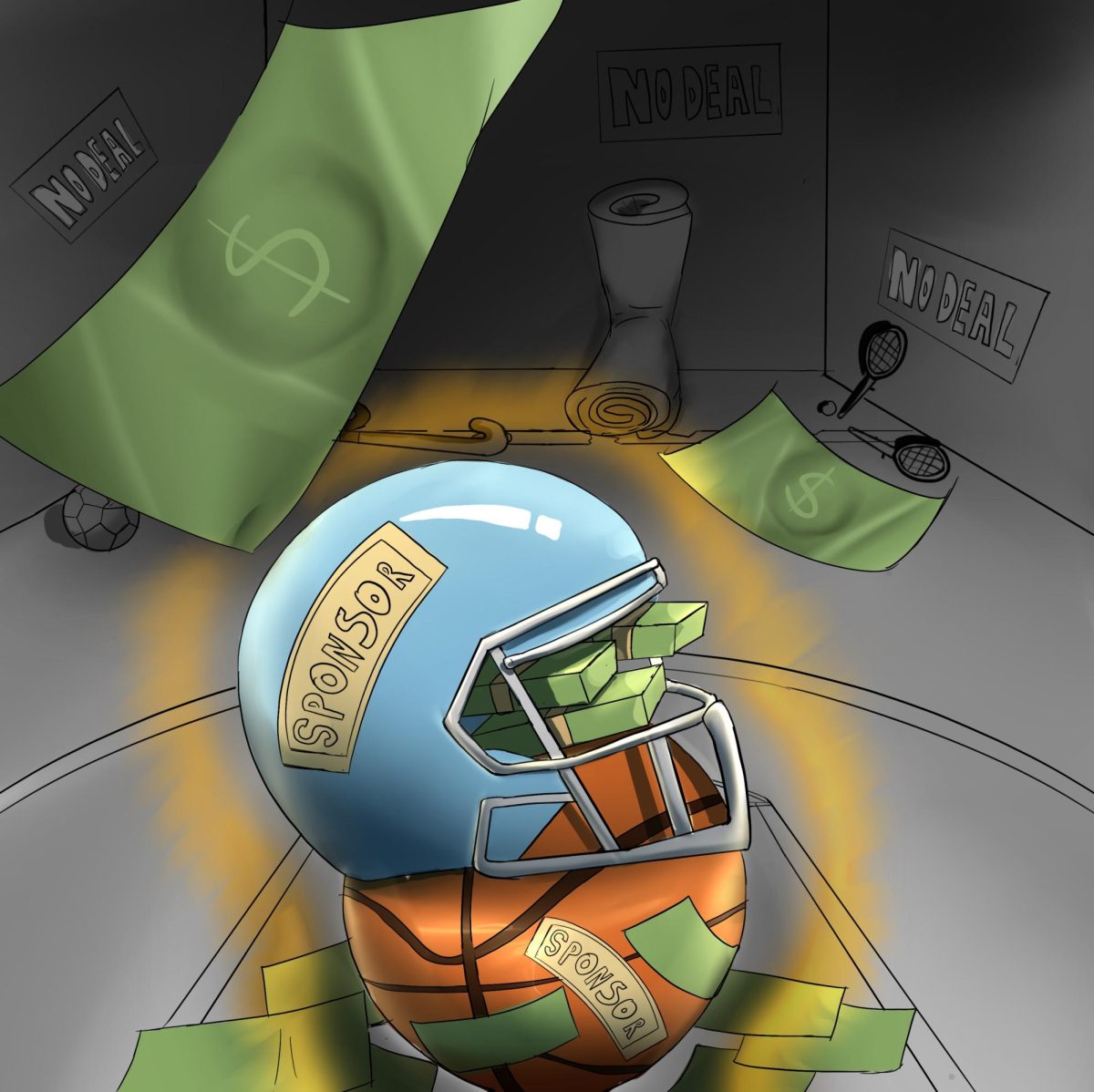

NIL or “Name, Image, and Likeness,” according to ESPN, is someone’s legal right to control how their likeness is utilized. Within the last three years, an NCAA rule change made it possible for athletes to utilize their NIL rights to obtain sponsorships and funds.

According to Inside Higher Ed, however, southern states such as Florida, Alabama and Tennessee, are abusing the idea of NIL money as a way of enticing transfer students and high school athletes. The biases of NIL money has already been apparent in its short history, with more biases sprouting every year it continues.

An 18-year-old football player who is receiving Division 1 sport offers is probably going to gravitate toward the school that is not only willing to pay for the tuition but also willing to hand them a luxury sports car and tens of thousands of dollars. Certain schools, however, want to control the offers their athletes can accept. According to ESPN, most schools need to approve the offers their athletes receive.

The world of NIL money highlights apparent partiality that influences the college decisions of athletes, either coming from high school or transferring. When looking at the article “On3 NIL 100” by On3, there are plenty of evident biases for what college athletes are being paid. These biases are damaging the reputation of the very recent system of NIL money for college athletes.

On the top 100 list, there are only five female athletes, four of them are basketball players and one is a gymnast. This gender prejudice is not only obviously unfair but is also creating more boundaries for Title IX.

Title IX, according to the Women’s Sports Foundation, is defined as providing female athletes equal opportunities in sports and educational institutions from elementary school physical education to college sports. Title IX law is meant to protect against gender discrimination, yet the NIL business is seen as discriminatory by its lack of providing financial assistance for female athletes. While it is understandable that Louisiana State University gymnast Livvy Dunne is making four million dollars from NIL brand deals, it is not fair that other women who are also great athletes in various sports are not given the same opportunities and deserved attention.

Another bias that is apparent in the NIL system is the favoritism for second-generation athletes. When looking at the On3 NIL 100 list, number one on the list, is the son of famous NFL and MLB player Deion Sander, Shedeur Sanders. Sanders, who is the quarterback for the University of Colorado Buffaloes, has made over six million dollars in NIL money through deals with brands such as Nike and Beats by Dre.

While Sanders is well-known in the college football world, he is definitely not the best quarterback in college football at the moment. According to ESPN, he is ranked third in passing yards and second in touchdowns while Miami quarterback Cam Ward ranks higher in both categories and is receiving significantly less offers. This is the same case as his brother Shilo Sanders, who is in similar commercials.

Sanders is a defensive back who plays for the University of Colorado football team like his brother yet does not put up much statistically, with only 43 tackles and zero interceptions this past season. But biases occur beyond the Sanders brothers.

ESPN reported that Bryce James, son of LeBron James, is not ranked highly as a high school basketball player, seeing that he is not in the top 100 list. Yet the already well-off high school student is provided over a million dollars by a multitude of brands simply because of his namesake. There are plenty of talented athletes in both high school and college who struggle financially and provide better statistics in their sports than these second-generation “stars.”

The brands offering deals to collegiate and high school athletes should consider offering financial assistance to local athletes as opposed to larger names who already have enough money. Unfortunately, the corporate side of brand deals is focused on promoting already well-known athletes instead of giving local talent their opportunities. If a local business in the Santa Clara area wants to advertise, why not pay a Santa Clara University girls basketball player, or an athlete from another sport from the local university.

Considering the world of NIL brand deals has been in place for only three years, it is surprising that they already have a mound of problems to solve, and the corporations should begin by addressing the obvious biases when it comes to where NIL money goes. Brands attempting to advertise should focus on promoting local athletes from close universities if they want to get a convincing voice for their advertisements as opposed to throwing money at an athlete due to their name status. If NIL begins prioritizing equal and fair representation rather than allowing greed and nepotism to run rampant, then perhaps by 2031, their tenth year of the program, athletes of all sports and genders can be given an equal presence.