Panou’s Paper Panel: The summation of Lermontov’s work

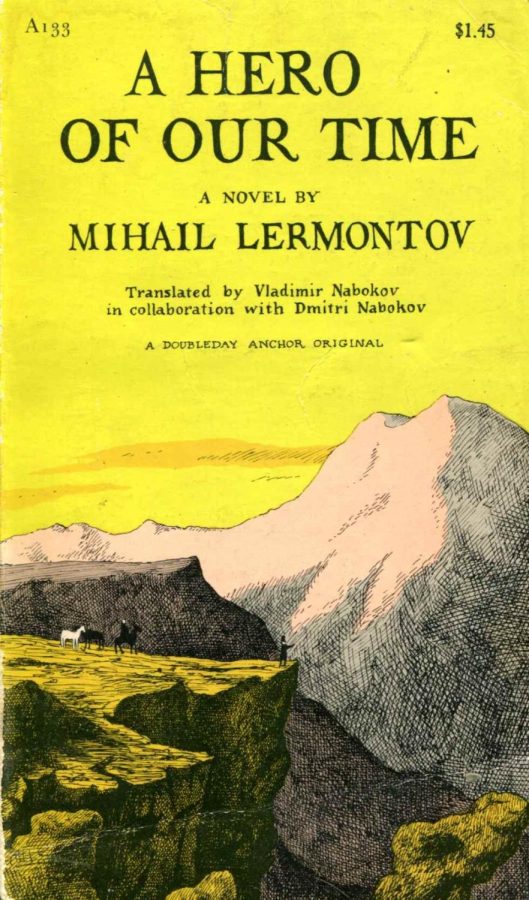

Mikhail Yurevich Lermontov’s classic, “A Hero of Our Time,” is widely recognized in the literary world.

Perhaps the embodiment of the grand duel between Russian literature and English literature, Mikhail Yurevich Lermontov is not only a grandiose figure in Western history, but a troubled and unique genius. He is most notably recognized for his classic, “A Hero of Our Time,” which is seen as his best work. The book was published in 1840, a time of great importance not only to literary history but also to world history. It is a tale of the Cult of the Self, embodying Romanticism and the absorption of its principles into Russian culture in an epic for the ages. A little bit of Lermontov himself died alongside the novel’s publication, and his work should never be forgotten.

“A Hero of Our Time” is set in the early 19th century in the Caucasus Mountains, a beautiful location renowned for its great mountains and picturesque landscapes. The Caucasus has attracted many travelers for centuries, including the novel’s unnamed narrator, who shares the story of his journey into modern-day Georgia from southern Russia. On his trip, deep into the mountains, the narrator meets a Russian military officer by the name of Maksim Maksimich, who then travels with him. Maksimich shares the stories of his youth, and one most peculiar to the mysterious traveler is the tale of a young, brash and arrogant military man by the name of Grigory Alexandrovich Pechorin. Pechorin becomes the hero of this tale, following him from his youngest exploits with a young Circassian woman to his final days, which carry a grand tale of betrayal and combat by honor.

There’s a grandiose characteristic behind “A Hero of Our Own Time” and its composition. The reader is able to feel an air of esteemed energy and relaxation alongside the novel. It’s a page-turner, written in an easy-to-read format, and there’s no question that it can enlighten and illuminate the reader with the writing style. Mikhail Yurevich Lermontov is a great author, but he and his novel were so much more than the work of a genius.

Lermontov himself was always a bit of a troublesome character. He was a tortured man, whose biggest enemy was himself, which drove him to dying at the age of 26. Lermontov was renowned as a unique figure, known for his brash arrogance and hot-headedness – the source of this youthful behavior would be his exploits and his profession. He was a soldier, who studied in St. Petersburg and Moscow alongside other notable Russian figures at the time. In his position as an officer, he considered writing to be a sideline profession – it was not as noteworthy as it would later be regarded as – yet Lermontov was renowned even beyond his own comprehension. He became famous for being Alexander Pushkin’s successor after his own death shortly before Lermontov’s. It is speculated that Lermontov wrote himself into “A Hero of Our Time” as the benevolent hero, Pechorin, and this is because of the sympathy he felt for Grigory Alexandrovich. Lermontov wrote that he was “ready to love the world, but no one understood [him].” His suffering takes the characteristic of what is not only his own greatest influence but the entirety of Europe at the time, Byronism.

Byronism was something unheard of before the benevolent Lord Byron. For many years, thinkers and scholars acknowledged that there was a fine line between idolatry and love, stemming from the Shakespearean age. Byron questioned the line. Where would the love for the divine stem from when love for a mortal idol became the new fanaticism? Byron wrote this among his journals:

They made me without my search a species of popular Idol – they – without reason or judgment beyond caprice of their Good pleasure – threw down the Image from its pedestal – it was not broken with the fall – and they would, it seems, again replace it – but they shall not.

Byron shattered previous ideas, and this spread across Europe like wildfire and most importantly to Lermontov, who idolized the man during his studies. The works of Lermontov and especially “A Hero of Our Time” emboldened Byronism, with the psychological question of love, idolatry and fanaticism. So of course, Byronic literature took a focus of one of these mortal idols and placed them in the limelight for all to see. The typical Byronic hero was one who was brash, arrogant and outcasted from typical social ideals – Pechorin – and would eventually meet an end by their misanthropic practices exacerbated by their own lackadaisical cynicism. Pechorin dueled for honor, he sought love interests, he was a hero by the greatest standards of benevolence, like that of Lermontov and Lord Byron. This taste of Byronism in Russian literature was uniquely Russian by itself.

Throughout history, Russian culture has been noted as one of the most fascinating and exciting, and looking at Russian Romanticism and Lermontov-style Byronism, it is clear to see why. The Russians took Romanticism and absorbed it, and they introduced the coldness of Eastern European culture into it. While typical Western European Romantic novels took the focus and placed them on the mystery and dominance of nature over man, Lermontov did the opposite. He knew exactly the dangers of cold mountainpasses, of brutal seas, and he highlighted it without mystery. Western European sources took the mind itself and made it a source of inspiration and of mysticism, but Lermontov and Russian scholars crafted stories of several, intersecting and self-sufficient characters whose intention behind their writing would not at any time be unknown to the reader.

It is not unique that the question of love, idolatry and fanaticism should be rehashed in these times. While Byron and other Romantic thinkers fit these questions into the scholarly tribunes of their time, they are making their comeback in a sorely divided America. In the name of fanaticism, in their own idol’s desire, rioters broke into and defiled the sanctity of the United States Capitol Building; politicians are being treated as supreme beings; healthcare rights are being restricted and stolen in the name of idolatry; and arrogance prevents some from making the right decisions in the name of inoculation and safety. While thinkers now ask these questions from secular standpoints, the inspiration from novels such as “A Hero of Our Time” and Romanticism is still there. Where will the line be drawn? It is to the people of these times to find the right decisions out of the many poor ones, to shatter the images of their liking held high on pedestals.